PTSD & Complex Trauma

“Traumatized people become “stuck” in the horror they endured. Traumatic memories dominate the life of many survivors, who continue to live in fear and feel tormented, even when the threat is long gone. Their body and mind feel and act as if an ongoing threat endangers their survival. At the core of psychological trauma is the confusion of past and present.”

Schauer, Neuner & Elbert, 2005

Types of Trauma Symptoms

Generally, practitioners may distinguish between Simple and Complex Trauma, or PTSD I and PTSD II.

PTSD I may develop after a single incident or multiple single incidents such as a Road Traffic Accident (also known as a “large T”), and is largely fear-based.

Complex Trauma can develop as a result of prolonged and repeated incidents where an individual knew these would re-occur, but was helpless and horrified and unable to stop it from happening. Examples of this are witnessing or being the victim of domestic violence or emotional, physical or sexual abuse, or neglect, during childhood (also known as “little T’s), with the emotions typically occurring being anger, shame, grief, guilt and disgust.

There are numerous symptoms commonly associated with these, some of which may occur soon after the trauma and some develop over time.

The four major categories include:

Re-experiencing

the event

Spontaneous memories of the traumatic event, reliving the event as if it were happening now, recurrent dreams or nightmares related to it, flashbacks, or other intense/prolonged psychological distress.

Hyper-arousal

Sometimes reckless or self-destructive behaviour, aggression, sleep disturbances, hyper-vigilance, shallow breathing or racing heart or related problems.

Avoidance

Trying to push away or avoid any distressing memories, thoughts, feelings or external reminders of the event.

Negative thoughts

and mood

Feeling numb, blaming oneself or others, feeling distant and cut off from others, loss of interest in previously enjoyable experiences, and inability to remember aspects of an event.

All about the DSM

The DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) is the reference manual that is used by psychiatrists and other health professionals to diagnose mental disorders and was created by the American Psychiatric Association.

It was first published in 1952 and not until 1980 was PTSD (Post-traumatic Stress Disorder) added.

Since then there have been various changes over the years.

The DSM 5 does not distinguish between PTSD and Complex Trauma.

The DSM 5 also added a new category known as PTSD Dissociative Subtype - Symptoms of Dissociation include feeling that the world around is not real or seems distorted, detachment from one’s own body, dreamlike states and de-personalisation.

Dissociation is common in survivors of Type II trauma as it serves as a coping mechanism when a person is unable to fight or flight.

Symptoms of PTSD

For a diagnosis to be given, a survivor must have had the symptoms for more than 30 days and either directly experienced, witnessed, or heard about the trauma to a loved one, or been exposed to trauma of others (such as emergency response units).

Symptoms of Complex PTSD

There are seven key areas of impact:

- Chronic difficulties in emotion regulation and compulsions, anger and rage, self harm and suicidality, impulsive behaviour and risk taking;

- Alteration in attention or consciousness as in amnesia, dissociation and/or depersonalisation, including Dissociative Identity Disorder

- Somatisation can include chronic pain, problems with the digestive system, fatigue, cardiopulmonary symptoms, headaches, nausea

- Alteration of self-perception – a sense of self characterised as feeling defective, like a failure, chronic shame and guilt, self blame, feeling alone and misunderstood

- Alterations in perception of the perpetrator – a distorted view of the perpetrator, such as idealisation, distorted beliefs or obsession with causing perpetrator harm

- Difficulty with interpersonal relationships – lack of trust, vulnerability, withdrawal, revictimisation or victimising others

- Alteration in systems of meaning such as faith, a sense of hopelessness and despair.

The symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are well defined and respond well to psychological treatment. However the role of complex trauma, particularly that occurring in childhood, is becoming associated with an increasing range of psychopathology and can perhaps best be understood as a spectrum of conditions rather than a single disorder.

Early adverse childhood experiences can disrupt the healthy development of a child, particularly in terms of attachment.

It is in many cases a caregiver who inflicts abuse, thereby impacting on the sense of self and others.

A child may grow up feeling there is something fundamentally wrong with them and believing that others cannot be trusted or be relied upon.

The seven areas of impact have been suggested by a variety of researchers and therapists (e.g. Roth et al 1997, Herman, 1992).

Dissociation

Dissociation is part of our survival instinct when we cannot fight or escape any other way. It is a mechanism that allows us to temporarily escape distressing experiences, emotions, sensations and thoughts. This can happen without conscious awareness.

Examples of dissociation are:

- Amnesia: Can’t remember incidents or experiences that happened at a particular time, or can’t remember important personal information.

- Depersonalisation: A feeling that your body is unreal, changing or dissolving. Out of body experiences such as seeing yourself watching a replay.

- Derealisation: World seems unreal. May see objects changing in shape, size or colour.

- Identity Confusion: Uncertain about who you are or struggling to define self.

If dissociation is not treated it can become a way of dealing with minor stresses and problems. The continued use of dissociation as a way of coping with stress interferes with the capacity to fully attend to life's ongoing challenges and can lead to:

- Constriction: Our awareness of events is blunted, as well as our emotions. A person will have a hard time focussing or concentrating, will see and hear less clearly, and be easily distracted.

- Withdrawal and Avoidance: A person will withdraw more, perhaps becoming socially isolated, and put a lot of energy into avoiding reminders of the trauma.

- Detachment: Time seems distorted and people are not aware of their boundaries so they can be clumsier and be injured easily.

- Rigidity: Sometimes in order to cope, people will gravitate to the other extreme of being super-organised and seem over-controlling of oneself and/or others.

Traumatic experiences shake the foundations of our beliefs about safety,

and shatter our assumptions of trust.

In order for the experience of an event to be traumatic it does not have to directly affect a person - witnessing or even hearing about an event can be considered to be exposure to a traumatic event. It is often the meaning or perception of the event that is more significant than the actual severity of incident.

Often people cope in very different ways, some coping strategies or coping behaviours may be more effective than others…. In other words, trauma is defined by the experience of the survivor.

Two people could undergo the same noxious event and one person might be traumatised while the other person remained relatively unscathed.

Some people can be high achievers and high functioning yet suffer the effects of Complex Trauma throughout their life, and might not even be aware of this. Others have more developed symptoms of PTSD and may have other co-occurring disorders such as self-harm or addictive behaviours in order to help them cope.

Some people may have no family or support system and may be homeless. Most people experience a sense of isolation and aloneness.

Most people who are exposed to trauma will experience a stress reaction – this is entirely normal as our bodies through years of evolution developed the fight-flight or freeze response.

Does Everyone Develop PTSD?

It is estimated that roughly between 10 and 20% of people exposed to a traumatic event will subsequently develop PTSD. Researchers are busy trying to elicit what pre-disposing factors may influence its development.

Some things that increase the likelihood of developing PTSD are:

- Freezing in response to trauma – those who become immobile in the face of severe threat as an instinctive survival technique

- Previous history of trauma

- Greater distress at the time of trauma and immediately thereafter

- Dysfunctional family

- Pre-existing psychological disorder

- Poor coping skills

- Age – younger or older people are at greater risk

Whereas most people recover from trauma after a period of time, a small minority go on to develop symptoms of PTSD, which can be of varying intensity, some may lead to minor difficulties whereas severe symptoms can be severely debilitating in every area of life.

PTSD is treatable.

There are a number of interventions available that have been shown to markedly reduce or even eliminate the symptoms of PTSD.

Although we cannot change history, we can change the way your history affects your life now. You can recover from your traumatic experience(s).

Trauma symptoms are probably adaptive, and originally evolved to help us recognise and avoid dangerous situations.

This is not a condition you need to live with forever.

Complex PTSD and Attachment

This form of trauma usually starts in early childhood and is characterised by harmful and persistent emotional, physical and/or sexual abuse, although complex Trauma can occur after any prolonged exposure to trauma.

In a secure and loving household children neurologically develop a 'learning brain', while those who have grown up in abusive households develop a 'survival brain'.

Our early experiences of care can often affect how we feel about ourselves and impact on the relationships we form with other people. People who experience abuse in what is meant to be a caring relationship can often feel that it is their fault and think badly about themselves.

They may also believe that all relationships will be similar and accept this or believe that it is better to be alone. Some people report that experiencing one traumatic event after another can make them feel powerless and helpless and there is no point trying to get help because there is nothing they can do.

Complex Trauma often produces feelings of fear, guilt, sadness and despair that can often be difficult to manage and control.

Often these feelings start suddenly and become overwhelming. Sometimes people report that the only way they can cope or find any relief is through drugs and alcohol or other forms of self-harm.

A complicated association between love and violence can develop in someone who was sexually or physically abused when young. The difficulty is understanding the connection between current behaviour and past trauma.

“Complex Trauma and PTSD are not specific to veterans or soldiers returning from war, but can affect people from all areas of life.”

Usually the person has no idea why they keep behaving a certain way. With trauma our memories are affected and much of the detail has been 'forgotten'. Therapy is helpful in making the link between the past and present.

Lack of trust in other people (and the world in general) is central to complex PTSD. Treatment often needs to be longer to allow you to develop a secure relationship with a therapist so you can experience that it is possible to trust someone in this world without being hurt or abused.

Later Symptoms

These can occur without PTSD but they are commonly the result of severe trauma:

• Attraction to dangerous situations

• Addictive Behaviour (eating disorders, alcohol or drug dependency, smoking)

These symptoms tend to develop either months or years later.

• Exaggerated or diminished sexual activity

• Depression

• Excessive shyness

• Inability to commit

• Chronic fatigue, low energy

Many physical ailments such as migraines, immune deficiencies, chronic pain, skin problems, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, severe premenstrual syndrome, asthma, back pain and chronic fatigue.

Being exposed to trauma can result in increased anxiety and depressive symptoms, feelings of guilt and shame, increased anger and resentments or a sense of betrayal.

Through specialised assessment, many personality disorders, particularly Emotionally Unstable/Borderline Personality Disorder, can be understood and therefore treated in the framework of complex trauma.

The world may no longer appear to be a safe place and the worldview may be shattered.

Usually these symptoms naturally ease off after a while, and there seems to be evidence to suggest that various factors such as a supportive family and friends may increase resilience.

Co-occurring disorders

Anxiety

Anxiety is a common and natural response to a dangerous situation.

For many it lasts long after the trauma ended. This happens when views of the world and a sense of safety have changed. You may become anxious when you remember the trauma, or sometimes anxiety may come from out of the blue. Triggers or cues that can cause anxiety may include places, times of day, certain smells or noises, or any situation that reminds you of the trauma. As you begin to pay more attention to the times you feel afraid you can discover your anxiety is really triggered by things that remind you of your trauma.

Anger

If you are not used to feeling angry these feelings may feel foreign to you, and you may not know how to deal with them. In therapy, you will be able to explore your anger and what you are angry about in a safe environment with your therapist who will understand and support you. You will learn that the anger is often triggered by subtle reminders of the trauma, and by your thoughts about the unfairness of the trauma, and you will learn ways of dealing with these memories and thoughts.

Common Stress reactions affecting our emotions:

Anxiety and Fear

We might feel jumpy, hyper vigilant, tense, fearful, easily startled at a sudden or loud noise

Irritability or Anger

We might fly into a rage more quickly, lose patience, be irritated at people we usually care about

Depression and Low Mood

We might feel tired all the time, or numb, have bouts of crying, lose interest or enjoyment, deep sadness or grief particularly if we’ve lost someone

Guilt and Shame

Sometimes we might experience survivor guilt – guilt at the fact that we survived and others may not.

We may blame ourselves, or feel we did not do enough to prevent the event, or feel shame for acting in ways we would not normally behave

Guilt and Shame

Trauma often leads to feelings of guilt or shame. These may be related to something you did, or did not do, in order to survive or cope with the situation. It is common for people to go over and over what happened in their minds.

You may find yourself going over steps you might have taken to prevent the trauma from occurring, or different ways you might have reacted.

You may also blame yourself for not having been able to put the trauma behind you and get back to normal, rather than understanding your symptoms as a normal, human reaction to intolerable stress.

Equally, others may not understand the nature of post-traumatic stress, and give you the message that you should be pulling yourself together and getting on with life.

Self-blaming thoughts are a real problem, because they can lead to feeling helpless, depressed and bad about yourself. In therapy, you will discuss these thoughts with your therapist, and learn to be less hard on yourself.

You will discover that you had good reasons for the way you behaved at the time.

Depression and Low Mood

Another common reaction to trauma is sadness, or feeling down or depressed. You may also feel that life is no longer worth living and that plans you had

made for the future no longer seem important or meaningful. With therapy, as you work through the memory of your traumatic event and start reclaiming your life again, you will find that your mood will also improve.

Addiction and Substance Use

The relationship between Trauma and Addiction or Substance Misuse is well documented. Some studies suggest that up to 34% of people in treatment for Substance Misuse have underlying PTSD issues, and between 30 and 59% in women. Alcohol and drugs numb the pain, often very effectively. Unfortunately this is only temporary and brings with it its own set of difficulties.

Traditionally it has been argued that individuals need to address their substance use first, before dealing with any trauma. However, alcohol and drugs are a coping strategy, and there is some evidence to suggest that abstinence from substances not only doesn’t resolve PTSD, but some symptoms may become worse. This often makes it very difficult for individuals to address their problem. Furthermore, substance use increases vulnerability to repeated traumas and also increases the likelihood of traumas occurring even without prior trauma history – addiction in itself can be traumatic.

A bit about the brain

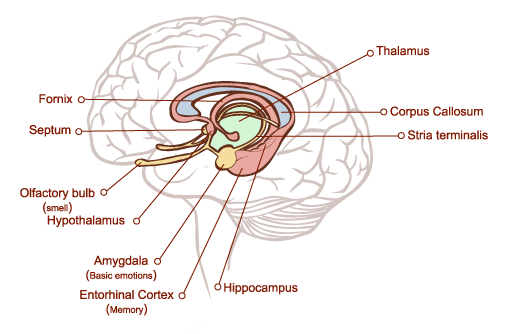

When we are born we have about 100 billion brain cells. These are called neurons. They are the most important cells in the brain. Neurons communicate with each other through chemicals (known as neuro transmitters) and electrical charges. In order to talk to each other they develop connections – these are called synapses. By the time we are 3 years old we have 1000 trillion synapses! Neurons are very vulnerable – they can only survive for a few minutes without continuous nourishment and oxygen. The most important job of a neuron is to help the brain and the overall system to survive. The Brain is the headquarters of our body and different types of memory are stored here. There are three main areas in our brain:

The Brain Stem

The brain stem (also referred to as the reptilian brain) sits at the base of the brain and regulates such functions as reflexes, sleeping, our temperature and breathing. In evolutionary terms it is the oldest part of the brain. Lizards and other reptiles have a brain stem which regulates these activities but their brains did not develop much further than that.

The Neo Cortex

The Neo Cortex (also known as the rational or thinking brain) is the last to develop and changes throughout life. It also has many different parts with more complicated names like “Orbitofrontal cortex”, which can be seen as the Manager of it all. It has many different jobs to do, and is where we think about things. Really, the neo cortex is thin and flat, but it crunches together to fit in the skull and has lots of folds and creases. It stores all the memories like facts, names, songs, remembering faces and the times tables. Also our goals and motivations and hopes for life. Most mammals have some level of neo cortex, the chimpanzee and dolphins have lots, but humans have much more, which makes us able to adapt to our environment and work things out, like inventing stuff like cars and computers.

How the brain develops:

When a baby is born the brain is ready for use – however it has not yet made many connections between the neurons. In fact neurons early on wander around, looking for connections and a purpose, those that don’t find one eventually die off, but the brain is not worried about that because we have so many. How these connections are made and what they look like depends on what happens in life. A good way to understand this is to think of all the billions of neurons as being connected with roads. The more some roads are used the bigger and stronger they will be. Those with little traffic will be no more than dirt tracks, others will become huge 6 lane motorways like the M25. So the brain literally builds itself around experiences. The different parts of the brain form memories. As our thinking brain takes the longest to develop, early memories are formed mostly in our emotional brain.

The Limbic System

The Limbic System (also known as the emotional or feeling brain) sits atop the brain stem and consists of many different elements such as “Hippocampus” and “Amygdala” (see diagram). These parts have many different functions, like remembering movement, attachment and dealing with emotions and feelings like fear, anger and love. It is responsible for keeping us safe in times of danger by causing the body to run, fight or freeze (more about that later). All mammals also have developed this Limbic Brain.

Fight, Flight, or Freeze

Research has shown that during trauma the only parts of the brain which are activated are the brain stem and some parts of the limbic system. The cortex, which is the part of our brain that allows us to think, plan and make decisions is largely shut down.

Two brain structures within the limbic system that play an important role in PTSD are the amygdala and the hippocampus.

The amygdala activates the body's alarm system. When activated by stress, the alarm system causes the body to fight, flee or freeze (flag, and faint)

This occurs instinctively and before we can consciously respond to a threat. The amygdala also processes emotional memories.

The hippocampus is responsible for processing information about your life and experiences and storing it away in long term memory for later use. Under normal circumstances, these regions communicate with one another and with the rest of the brain in a smooth fashion. However, traumatic stress disrupts the communication between these different areas. The logical, rational parts of your brain cannot get the message through to the amygdala that the danger is over and it's okay to relax.

The hippocampus cannot take the emotional information processed by the amygdala and store it away as a long term memory. So your memories of trauma stay with you all the time and you continue to feel as if you are in constant danger. It’s as if the person is right back in the traumatic event without a beginning, end, or even the knowledge that they survived. This is not a conscious process and we cannot think our way out of this.

When the danger is over, the alarm system is supposed to shut down, allowing the body to relax and return to normal. However, traumatic events can impair the functioning of the alarm system so that you cannot tell when the danger is over and your alarm system does not shut down properly. You continue to feel as if the danger is ever present, which promotes a state of chronic hyperarousal.

The flight, fight and freeze responses continue to play out even when the original trauma has ceased because we’ve not able to store the information in a rational, chronological way. Our bodies and brains react as if the trauma is still occurring. The trauma first affects our bodies instinctually but then expands to our minds and emotions.

When the brain perceives a threat, the amygdala becomes active and sends messages to the rest of the body to prepare for danger. Neurobiological Research indicates that the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis are responsible for stress regulation and are implicated in the development of PTSD.

The normal response of the body to stress is to activate both the glucocorticoid as well as the adrenergic systems (also known as sympathetic nervous system). During this process both cortisol and norepinephrine are released, cortisol acting as the brake and norepinephrine as the accelerator. When stress abates the systems return to normal. In PTSD this process has somehow got dysregulated, and the brakes don’t work. The stress chemicals produced in your adrenal gland travel through the bloodstream and effect your whole body. In your brain, they inflame the amygdala (increasing the intensity of grief, terror, and rage). They block the hippocampus from laying down and recalling memories. If these chemicals continue for a prolonged time, the hippocampus may shrink and the amygdala will enlarge. (You can see these changes on an MRI brain scan.)